US President Donald Trump has been signalling his determination to regain control of rare earth minerals—critical to powering everything from new energy to computing. Their name notwithstanding, rare earth minerals aren’t that rare. They are toxic and dangerous to process, however, which is why American industry gifted their production to China in the 1980s.

In this episode of ThePrint Explorer, Praveen Swami looks at the geopolitical struggle to secure these crucial elements.

New Delhi: The placards in the photograph seem to plead with history. “Your wives and babies may be next,” one states. Another held up by a young girl proclaims, “Iron spells tragedy.”

Late in the summer of 1937, the Imperial Japanese military had invaded China, murdering its way through the country’s villages and towns with a savagery rivalling that the Nazis would soon bring to Europe. In February 1939, when the ship “Norway Maru” pulled up the port of Astoria to pick up a cargo of scrap metal, several dozen ethnic-Chinese lined up on the docks to protest.

Even in America, trade unionism was a big deal in those days, and the longshoremen responsible for loading the Japanese ship refused to cross the ethnic-Chinese picket-line. The management threatened to fire them, but a compromise was hammered out: The “Norway Maru” would be loaded this once, but Astor port would handle no more shipments of iron scrap to Japan.

The United States wasn’t happy with the invasion by Japan, but their bilateral trade was, at that time, controlled by a 1911 trade treaty. Congress didn’t want to circumvent that treaty with an embargo on Japan. But public pressure built up—spurred, in some part, by missionaries and journalists reporting the horrors of the war.

President Theodore Roosevelt ordered a “moral embargo” against Japan on aircraft armaments, engine parts, accessories, aerial bombs and torpedoes. The “moral embargo” was soon extended to include molybdenum, aluminium and equipment required for producing aviation fuel.

Late in 1940, when Japan pushed south into Indo-China, the United States finally abrogated the treaty, and imposed embargoes on the export of all kinds of material, including on iron and steel scrap, and aviation fuel.

This story probably sounds familiar these days because it is. In response to new tariffs introduced by President Donald Trump’s administration, China announced it would, in retaliation, restrict exports of rare earth minerals, which are key to the manufacture of a swathe of high-technology civilian and military devices, including the phone or computer you’re watching this episode of ThePrint Explorer on.

For its part, Trump is about to sign a deal giving the United States a share of Ukraine’s rare-earths sales, and has even offered to buy Greenland, where there are large rare earth deposits, even though the one serious effort to dig them out ran into trouble because of the risks of uranium contamination.

In this episode of ThePrint Explorer, I want to look at why the geopolitical struggle to secure rare earth minerals is so fraught.

Also Read: Will Trump finally revive post WWII plan for Europe to create its own military

War and resources

In 1940, Imperial Japan correctly understood that the US embargo would kill off its ambitions to become the hegemonic power in Asia. Japan had no big iron mines or a way of making steel, and so, the ban on scrap was a direct attack on its military.

On 7 December, 1941, it made a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, hoping to destroy America’s carrier fleet. The attack failed and years of war followed, ending in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The war, it’s important to understand, was not just about scrap metal. It was also about nationalism and race. But it tells us how important resources are to shaping the actions of nations.

The story began long before anyone was worried about rare earth elements—which, for those of you who paid attention in Chemistry class, are the 15 elements in the periodic table known as the Lanthanide series, and a few more.

The story begins, as so many modern stories do, some time around 1945. The Nazis had raced east in 1942, to secure the vast oil fields of the Caucasus, but were defeated at its gates in the Battle of Stalingrad. The Wehrmacht’s defeat in the Second World War from then on was almost inevitable because it didn’t have enough hydrocarbons to power its war machine. You can’t fly fighters or drive tanks, obviously, if you don’t have any fuel to put in, and that’s exactly what happened to the Nazi military.

As an aside here, people used to claim that Adolf Hitler was a madman to begin a war on two fronts, and fight with the West and the Soviet Union at the same time. The truth, as military historians now understand it, was he couldn’t fight a war on one front alone because the energy he needed to fight it was on his east.

The United States, however, was able to make available enormous amounts of hydrocarbons available to its allies. The Soviet Union had its own vast reserves, and the British had their colonial fields in Iraq and Persia.

After the Second World War, the Great Powers basically carve up global access to these hydrocarbons—the petrol, diesel and natural gas that powers our world. “Persian oil,” President Franklin D. Roosevelt said to a British diplomat in 1944, “is yours. We share the oil of Iraq and Kuwait. As for Saudi Arabian oil, it’s ours.”

The Soviet Union was also an oil-exporting nation, which caused some economic problems of its own, but this meant it was happy to go along with this arrangement. In case someone in Moscow got any ideas though, Washington spelt it out. “Let our position be absolutely clear,” President Jimmy Carter said in 1980 after the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan, “an attempt by any outside force to gain control of the Persian Gulf region will be regarded as an assault on the vital interests of the United States of America, and such an assault will be repelled by any means necessary, including military force.”

In the course of the Iran-Iraq War, President Ronald Reagan used the US Navy to escort oil tankers through the Persian Gulf. In 1991, President George H.W. Bush had to send in the military to protect oil-rich Kuwait from Iraq ruler Saddam Hussein’s troops.

Doing all this costs a great deal of money. Hudson Institute scholar Arthur Herman, in a superb analysis, noted, “Keeping the region’s shipping lanes, including the Strait of Hormuz, open to tanker traffic costs the Pentagon, on average, $50 billion a year—a service that earns us the undying enmity of populations in that region.”

Princeton University’s Roger Stern has estimated that the US’s oil mission cost it $6.8 trillion from 1976 to 2007. “On an annual basis,” he noted, “the Persian Gulf mission now costs about as much as did the Cold War.”

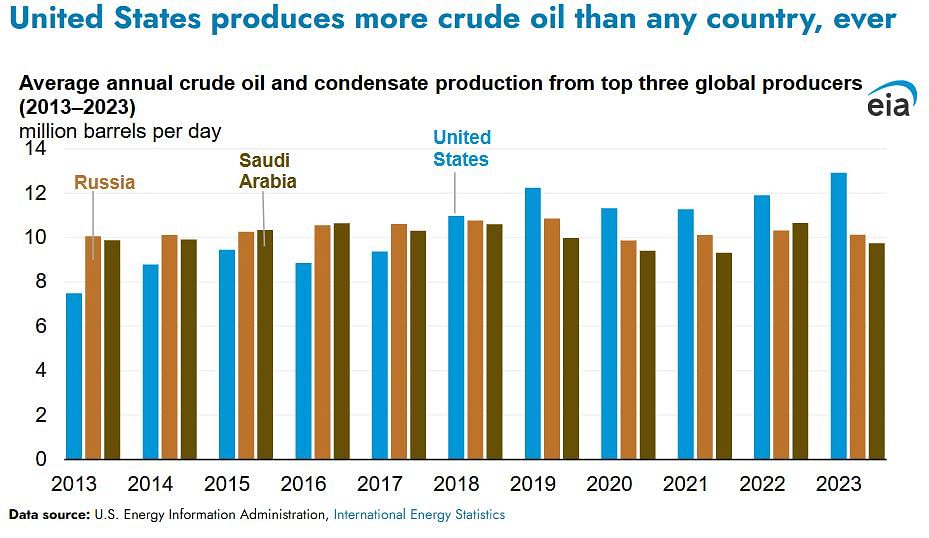

Look at this chart produced by the United States Energy Information Administration. Today, the United States produces more crude oil than any country has ever done. It doesn’t need Saudi Arabia or Qatar or Iraq to meet its own needs. Trump understands this, and I suspect there will be some interesting developments in the Middle-East as his cost-cutting shears fall on the US military.

The thing he doesn’t have though is rare earth elements. If you think your future is about robots and artificial intelligence and quantum computing, or even just about making better mobile phones, that’s a problem.

Also Read: How an American corporate corruption scandal in 1974 laid the foundations for Adani US indictment

How China became a rare earths empire

Besides the many blessings rare earths bring to our world, they also have a dark side. Few things are as toxic for the environment and dangerous for workers to produce. The process of mining generates dusts laden with radioactive materials. The refining process, which uses sulfuric or hydrochloric acid to separate the elements from their parent rock, spews dangerous chemicals into the soil and water.

The primary processing, the third stage, generates slag with high levels of radioactivity. Finally, there’s a problem of disposing of products with rare earth products. All can cause organ damage if inhaled or ingested, and five—promethium, gadolinium, terbium, thulium and holmium—can cause radiation poisoning.

The scholar Julie Michelle Klinger writes that in China, “radioactive rivers, cancer villages, acute chronic arsenic toxicity, and long tooth disease constitute an environmental and epidemiological crisis so grave and expansive that addressing it is now viewed as a matter of national security and territorial integrity.”

That’s why America gave the rare earths industry to China in the first place.

In 1982, the well-established Mountain Pass mine in Southern California had just completed a $15 million separation plant to allow for a 35 percent production increase. At the time, the mine was responsible for 70 percent of the annual global production of rare earth oxides.

Edward Nixon, the very Right-wing President Richard Nixon’s brother, had played a big role in founding the Environment Protection Agency. Edward Nixon argued that many of the more toxic processes involved in rare earths could be moved to China in order to reduce environmental liabilities in California and to save costs.

This, of course, neatly tied in with the outreach President Nixon’s government had begun with China, and which had flowered under the liberalising Chinese premier, Deng Xiaoping.

Around the same time, China’s Ministry of Finance, the General Administration of Customs, and State Administration of Taxation began offering rebates to Chinese companies and joint ventures for rare earth exports. This drew American FDI from companies wanting to process rare earths in China, and sell them back to the US.

Things came to a head in 1997, when the Mountain Pass mine was found to have spilled some 600,000 gallons of radioactive wastewater into the desert, leading to huge fines and settlements with potential victims. The mine halted operations after San Bernardino county authorities initiated a lawsuit for damages and issued orders for a cleanup. Mountain Pass moved its more dangerous operations to China, giving Beijing control some 97 percent of global rare earth production at the time.

A long line of companies followed in its footsteps. Magnequench, an Indianapolis-based company specialising in producing neodymium magnets, had relocated to Tinjian by 2003. The company shut down the last US-based factory used to make some of the magnets—a key component in American cruise missiles.

The benefits this gave to China are clear. In the 1990s, for example, the United States was still the front runner in what is called the “sintered rare earth magnet industry”. But when US mining of rare earths stopped, the magnet industry and the expertise left and moved mainly to the People’s Republic of China.

When the United States still maintained its cutting-edge on these magnets, it accounted for twelve of the industry producers. Today, China holds the dominant position in the industry. Chinese companies produce over 80 percent of each of the magnet materials, and there are only a few facilities outside China that retain the capability of processing rare earths on a commercial scale.

Thomas Jefferson, the American founding father, once observed, “Merchants have no country. The mere spot they stand on does not constitute so strong as an attachment as that from which they draw their gains.” To be fair to merchants, no one in the government or political class seemed overly bothered about this offshoring either. As long as the world was globalising and trade was free, what did it matter if some dangerous or toxic element was being processed in China or wherever else as long as it would be sold back to the US?

Shifting tide of geopolitics

Everything worked perfectly, until it didn’t. In 2008, the financial crisis threatened to tear out the heart of the United States economy, and governments around the world began to wonder what this meant for the global order.

China’s then prime minister Wen Jiabao, in a March 2009 statement, publicly voiced concern over the safety of the $1 trillion his country held in American government debt. The head of the People’s Bank of China Zhou Xiaochuan demanded changes in the international monetary system. To many in China, it seemed the crisis had given an opportunity to use their power more effectively to reshape the world order.

The first use of rare earths as a weapon came in 2010, when China began an informal embargo on some exports to Japan over a dispute over control of the Senkaku islands. There is, among experts, a considerable debate over just how tough this embargo was and what exactly was affected.

This much was clear though. From 2006, China had slowly begun cutting back its production of rare earths, and by 2010 prices had begun to skyrocket.

Earlier, China had tested the waters by restricting exports of other critical materials. In 2009, the United States, the European Union and Mexico launched a World Trade Organisation case, challenging China’s right to restrict bauxite, coke, magnesium, manganese and zinc exports. Again, China had cut production forcing prices to rise, just like the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) does with petrochemicals. On 30 January, 2012, a WTO panel ruled that China was in fact in violation of WTO regulations.

Scholar Sophia Kalantzakos notes in a book on the issue—China and the Geopolitics of Rare Earths—that China had, for all practical purposes, become a kind of rare earths OPEC of one. Japanese foreign minister Seiji Maehara, sharing a platform with then US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, reflected: “Even if this problem did not exist, to rely for 97 percent of these resources on China, as we look back, was certainly not appropriate, and therefore we have to diversify the sources of rare earth minerals.”

Fine. But how? That was 2010, this is 2025.

The 2010 crisis passed, and the issue slowly disappeared off the headlines, with little changing. In 2012, there were problems again. This time, the US, the EU and Japan chose to act in unison by simultaneously filing complaints with the WTO, demanding consultations with China over its restrictions on the export of rare earths, tungsten and molybdenum. The three powers alleged that China’s actions were not in line with WTO provisions, and complained about the imposition of export duties and tariffs.

The United States mounted pressure on China over the issue, and things seemed to have been sorted out for a while. That was until Trump announced his tariffs and China retaliated with its rare earth ban.

There isn’t a shortage of rare earths as such. They’re much less rare than the name makes them sound. China has the world’s largest reserves, but it is followed closely by the United States. Australia and India both have rich reserves of monazite, though there are some problems of extraction due to its radioactive thorium content.

The real issue is that China, because of its long experience, has developed a competitive advantage in the separation of these elements by mastering the metallurgy of their deposits. Once that competitive advantage is established, it’s hard for companies elsewhere to compete.

From history, we know that nations can act when they need to. The energy crisis of 1973-74 and 1979 showed US policymakers how crisis in the Middle East could jam the wheels of industry in their country. Action was taken to shore up strategic reserves and policies were designed to stabilise the region.

American domestic oil production stepped up. The extraordinarily high production we see in the US came under former president Joe Biden’s administration, which constantly marketed its desire to transition to alternate energy, but didn’t leave the country insecure.

Where all this leaves India isn’t clear. The country clearly needs the US’ support to ensure access to critical materials, at least in the short-term. Exactly what terms and conditions Trump might try to extract for that access, or for that matter China may ask for, remain profoundly unclear. India had to struggle in the face of the past oil crisis, which hurt its economy deeply. Rare earths could be the next long term headache policymakers need to start preparing to deal with now.

(Edited by Mannat Chugh)

Also Read: Exile of atheist poet Daud Haider shows Bangladesh wasn’t secular paradise even 50 years ago